Good afternoon, colleagues and friends,

Thank you for joining us today for the regional launch of UNFPA’s 2025 State of World Population Report here at the Third Ministerial Conference on Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) in Asia and the Pacific.

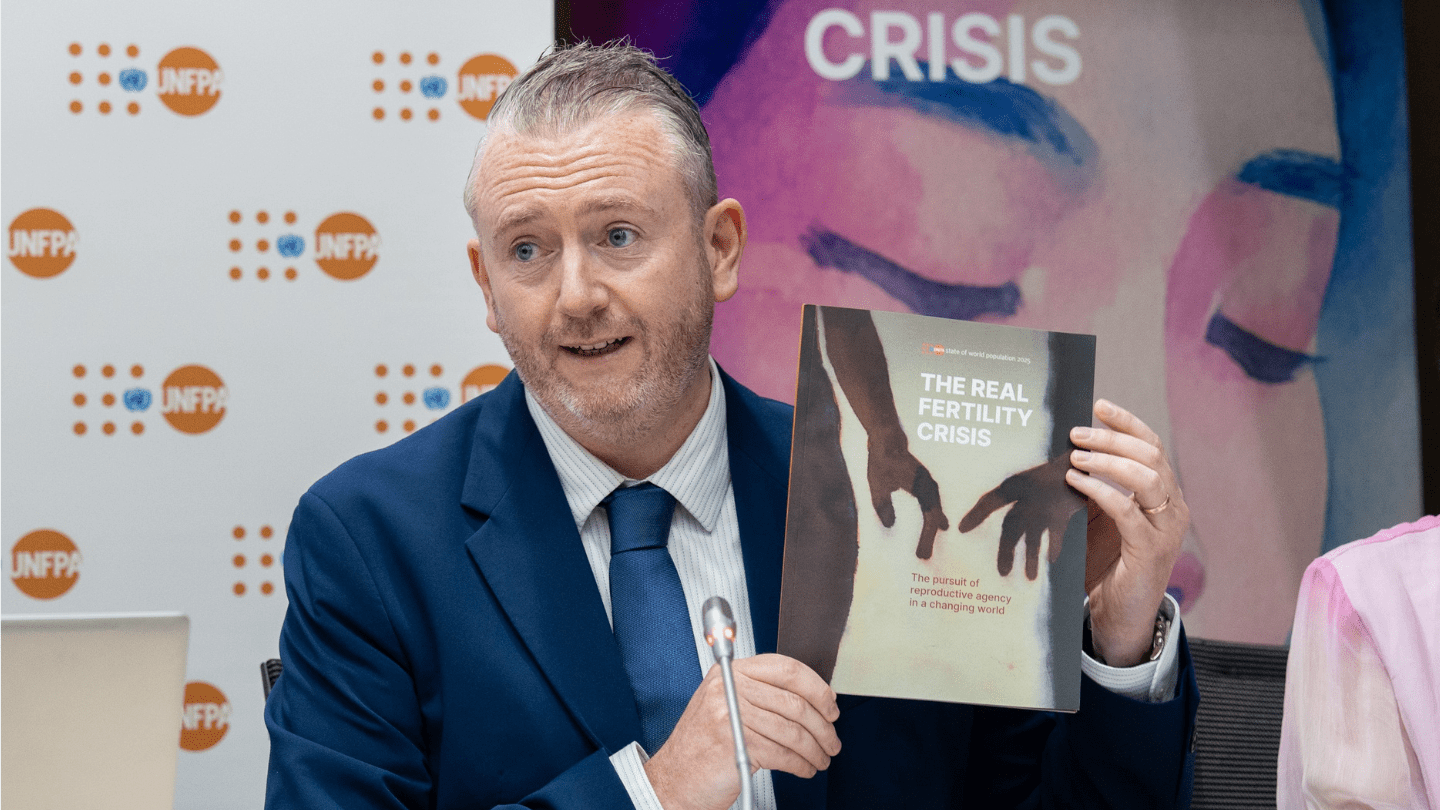

It is timely that we launch this report, “The Real Fertility Crisis – The Pursuit of Reproductive Agency in a Changing World,” at this side event, alongside a discussion on the vital role of CRVS systems in advancing gender equality. We are living in a time of demographic paradox. On the one hand, alarm bells are ringing over falling fertility and fears of a “population collapse.” On the other, the challenges of a growing global population continue to dominate headlines.

In Asia and the Pacific, home to over half the world’s population, these demographic dynamics are playing out in real time. CRVS systems, along with population data, are critical for monitoring these trends but more importantly, they ensure individuals are seen, that they are counted, and are able to claim their rights, including reproductive rights.

Fertility is declining across this region and the world for many different reasons. But the real fertility crisis is not about “too many” or “too few” births. It’s about whether people are able to choose whether to start or grow a family, on their own terms.

This year’s report draws on global survey data, along with a wide range of academic and policy research and lived experiences from communities around the world. Its findings highlight an important truth: There is no single fertility story in Asia and the Pacific; rather, the right to reproductive agency is universal.

In the Republic of Korea, fertility has fallen to just 0.8 children per woman, the lowest globally. This is not primarily due to a lack of access to reproductive health services, but rather to high housing costs, job insecurity and deeply entrenched gender norms that still expect women to choose between careers and caregiving. In contrast, for instance in Samoa, women, on average, have three or more children. Here, adolescent birth rates exceed 50 births per 1,000 girls aged 15 to 19, and unmet need for contraception reaches up to 27 per cent for women of reproductive age.

In parts of South and Southeast Asia, including Bangladesh, Lao PDR, Nepal and Timor-Leste, adolescent birth rates exceed 80 per 1,000 in some areas. Early marriage, social pressure, lack of comprehensive sexuality education and limited access to reproductive health services continue to drive many unintended pregnancies. Even within countries, we know that realities diverge based on socioeconomic factors.

An adolescent girl from a rural village may have no access to contraception and limited information about sexual and reproductive health, putting her at risk of early pregnancy. While a young woman living in the city may choose to delay motherhood due to economic pressure or job insecurity.

The bottom line? Both of these women are navigating systems that don’t fully support their individual choices.

True reproductive agency requires more than simply access to services. It depends on education, gender equality, economic stability, and the ability to make informed choices, free from stigma, violence, and especially free from coercion.

In the Maldives, fertility has fallen to 1.6, yet 20 per cent of women still face unmet need for family planning. Here in Thailand, where the fertility rate is 1.2, most people want two or more children – but actually they cannot achieve that aspiration, despite nearly universal access to services.

So, we cannot assume that birth rates reflect what people want. Many are still being left behind, especially adolescents, rural women and those facing social stigma due to age, marital status, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

Young people in particular face major risks. Across Asia-Pacific, over 40 per cent of adolescent pregnancies are unintended – and fewer than 1 in 4 unmarried, sexually active adolescents use modern contraception. These are not just statistics.

A few months ago, I met a 17-year-old mother in a remote part of Vanuatu. She had walked for hours to reach the nearest clinic. It was her first-ever contact with the health system. No contraception, no antenatal care, no support. Yet she still dreamed of continuing her education. Her aspirations – and the aspirations of millions like hers from all across the region – and these aspirations must shape our collective priorities. There is no excuse.

But we also see stories of progress in our region. In India, the world’s most populous country, three women of three generations from one family in Bihar told us a powerful story of how childbearing has changed over time. The grandmother had five sons before age 30, with no access to contraception or autonomy. Her daughter-in-law had six children under pressure to bear a son. Today, the granddaughter and her husband have chosen to have just two kids – supported by health workers, education, and their commitment to shared decision-making. This is what progress on reproductive agency looks like: one woman at a time, across generations. And yet, for too many, systems are still failing to keep pace with people’s evolving needs and aspirations.

What we see is not a crisis of birth rates. It is a crisis of systems failing people.

Too often, individuals are shut out of parenthood or forced into parenthood by unequal systems that restrict their choices. Across the region, women and girls continue to carry a disproportionate share of unpaid caregiving and domestic work, limiting their economic opportunity and reinforcing gender inequality. Women still do four times more unpaid care than men. As populations rapidly age, this burden is increasing, often without the support of adequate social protections or care infrastructure.

The report that we are launching today, finds that economic pressures – from unstable work and low wages to unaffordable housing – are among the top reasons people feel unable to form the families they want. So what we’re seeing is not just financial constraint, it’s also a generational shift. Take a woman here in Thailand. She and her husband, both well-educated with good jobs, still feel they can only afford one child. Meanwhile, their parents, earning far less, had larger families. Today, the cost of raising children has soared, but so too have the expectations, especially in urban, middle-income settings.

If we look at humanitarian settings, challenges are magnified.

Nearly half of all people affected by crises, whether from conflict, climate disasters, or displacement, live in Asia and the Pacific. Ours is the most disaster-prone region in the world. When crises strike, access to reproductive health services is often the first thing lost and the last to be restored. Those most vulnerable, including migrants, people with disabilities and those living in poverty, are the hardest hit.

We miss these realities whenever headlines and policymakers attribute falling global fertility solely to people “opting out” of parenthood. Our findings show the opposite: Many people are being forced into parenthood, and even more are being shut out of it, by factors that are beyond their control: economic hardship, climate change, lack of partner support, infertility, gender norms, and inadequate health systems. The real problem is indeed that systems are failing people, not the other way around.

Too many governments turn to policies that miss the mark. One-time baby bonuses, fertility targets, and restrictions on abortion or contraceptives, bans on sexuality education – all of these do not work. In fact, what is worse, such policies undermine rights and erode trust. History has repeatedly taught us this lesson.

We need to stop trying to “fix” fertility and instead invest in rights-based solutions.

We need to rethink how people are supported through the care economy. Instruments like National Transfer Accounts can help governments track and value care work and design policies that better support women and families.

Better data, including ethically sourced data on violence against women, can help governments build safer spaces for women and girls, both online and offline. Birth registration helps establish a person's legal age and prevent child marriage.

At UNFPA, we advocate for increased investments in reproductive autonomy, irrespective of a country’s fertility rate.

Across Asia and the Pacific, we are working to support Comprehensive sexuality education and rights-based, youth-friendly health services to advocate for affordable housing and parental leave.

As well as advocating for policies that support, not restrict, diverse families – and we are relentless in our work on ensuring strong responses to gender-based violence, including in digital spaces, where online harassment increasingly isolates women from the connections that shape their lives.

At UNFPA we advocate strongly for systems that recognize and count every person. CRVS systems are foundational to rights and recognition, and an integral part of that promise of the SDGs to leave no one behind. When births, deaths, and marriages go unregistered, girls and women are denied services. Unregistered marriages can conceal child marriage. Unrecorded deaths from gender-based violence can erase the scourge from public view. By granting all individuals their legal identity, CRVS systems empower people to exercise their rights, including reproductive rights.

That’s why UNFPA, with support from our partners, is working with governments to build inclusive, gender-responsive CRVS systems across this region. Because when people are counted, when they are supported, and when they are seen, then they can make choices about education, about careers, and about parenthood, and they do so with dignity and freedom.

Let me close with the words of a young person who spoke to us as part of our global survey of the report we are launching today, who said: “Before I bring a child into this world, I have to fight for the right to do so on my own terms... This isn’t just my fight. It’s the fight of billions of young people trapped in systems that deny them the rights and dignity they deserve.”

Let’s ensure that we hear that call.

Let’s build a region where every young person has the freedom and support to plan their future – where parenthood is a choice, not a burden or a risk – and where hope, not fear, shapes the next generation.

Thank you.